John Carpenter has a penchant for bringing well-oiled technical chops and studious thematics to schlocky, genre-driven films with mass appeal. What’s always struck me about his films is the overwhelming sense of claustrophobia that persists throughout each one. This is just as apparent in Prince of Darkness (1987) as any of the other bigger ticket films in his repertoire like Halloween (1978), The Thing (1982), and They Live! (1988). In Carpenter’s world, we are trapped, by whatever metaphysical forces pull a serial killer back home, by systems of oppression maintained by a clandestine alien race, and in the case of Prince of Darkness, by the Devil himself. Whatever the cause, the camerawork in Carpenter’s films bears out this pervading stuckness.

In service of this sense of confinement, Carpenter’s mise is defined by an economy of space. His settings are mostly (with some exceptions) limited to cities and suburbs, the camera winding down alleyways, between houses, down hallways. This presents a paradox, of pinned in blocking met with often fluid camera movements, which in turn outlines a professional mantra: make the most with what you’ve got. The famous example here is the opening tracking shot in Halloween, a slam-bang bit of auteurism in a lower budget slasher that helped define a new technical innovation (as well as a few careers). But Carpenter’s films are marked by “no exit” compositions across films under his two most frequent collaborating cinematographers, Dean Cundey and Gary B. Kibbe, implying that it’s a preoccupation of the director that is borne out by the stories that he shows and tells.

Hardly a marquee title in the Carpenter pantheon, Prince of Darkness still provides evidence for the claim that the director’s films are defined in part by their claustrophobia and overall use of space. The story defies quick categorization, but the gist is that a mysterious canister in the basement of an abandoned LA church draws the attention of the archdiocese and an interdisciplinary team of professors and graduate students, analysis reveals that it contains the liquid essence of Satan, and signs point to a still more powerful and ancient evil reaching out to awaken this force so that it can subsequently join our world and bring about Armageddon. Elements of techno-horror, possession, and zombie apocalypse are all in the mix, a swirl of haunted computers, murderous shuffling hordes of homeless paeans, and demonic prophecies. Containment (or lack thereof) is key to the plot, as the action is propelled by the liquid’s leeching out from its confines, and the “father of Satan” über-demon inches ever closer to escaping the mirror world that serves as its prison. Spatial limitations dominate the film, as the church and its immediate surroundings serves as the sole setting for 2/3 of the story. It’s no wonder that this church has become a destination for Carpenter pilgrims, and even hosted a screening of the film back in 2015. These characters are locked into their spiritual battle with no hope for escape, and Kibbe drives this point home with a wealth of shots that increase the claustrophobic tension in their composition well before the team digs into their spiritual battleground.

In the opening minutes of the film, Donald Pleasence’s unnamed priest is introduced to us as a man hemmed in by his duties, as he deliberates with his fellow clergy in part of a dialogue-free montage.

For a passing moment, he stands framed by bars and columns, shadows stretching towards the near-pitch black void that the holy men keep behind them. A bit later, as he approaches the church for the first time, the spiritual prison grows around Pleasence as bars fill the frame entirely.

This technique recalls the framing traps set by film noir cinematographers, achieved mostly through chiaroscuro lighting, that were meant to imply or presage the doomed outcomes of their criminal subjects. The priest’s imprisonment is brought on by a crisis of faith, as he faces an ontological dilemma that can only be addressed by synthesizing his biblical study with theoretical physics and computer engineering. But again, this shot and the one above present a paradox of kinetic stasis, as the camera moves in a continuous pan across the trapped Pleasence. It is the same paradox of constricted, perpetual motion seen in a swarm of ants in the beginning of the film (a flourish reminiscent of the opening minute of Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch [1969]). This fluid sense of encroachment and restriction is not limited to the priest, as others get caught in Kibbe’s cross-hairs.

As our de facto main character Brian Marsh (Jameson Parker) heads out of class one night, he catches sight of love interest Catherine Danforth (Lisa Blount) cutting her way across campus. Even here, an ostensibly gentle moment in an idyllic setting, the camera packs in some voyeurism and paranoia, tracking Catherine on her walk and briefly trapping her in the gap of a tree.

This quotidian dread recalls the clash of comfort and violent confrontation at play throughout Halloween. It also brings a bit of menace to Brian and Catherine’s romance, a strange and stilted relationship that is left at an eerie impasse at the end of the film. Catherine is visibly suffocating under the patriarchy, as most of her interactions with Brian end with him guffawing his way through sexist presumptions and her getting morose and aloof. Again, this is claustrophobia in motion, a moment of ephemeral containment that is over just as soon as it begins. If the panning underscores the fluidity of these characters’ constraints, the camera’s tilts show their divine (or cursed) provenance.

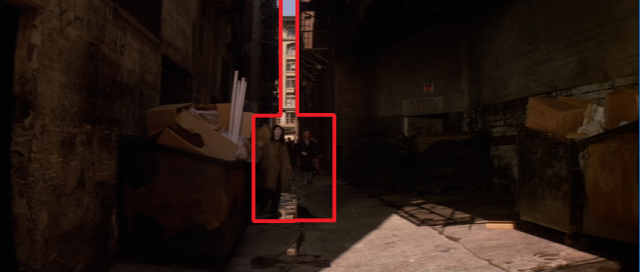

The camera drifts up and down at several key points throughout the film, but my favorite example is the shot that serves as the starting gun for the second act. After the crew is assembled for their unholy research project (and directly after Brian and Catherine consummate their awkward affair), the film cuts to the top of an alley outside of the church. A slow tilt makes its way down the seam of the alley, and the score picks back up as special guest ghoul Alice Cooper steps out from behind a dumpster.

The beauty of this scene is really in its motion (I tried to make a GIF but it didn’t pan out, no pun intended), but you can still get a sense for the symmetry of the blocking in this frame. In a film about the battle between evil and those that wish to keep evil contained, the metaphoric weight of consistent camera tilts is hard to ignore. And this being a Carpenter film, there’s probably some sociopolitical messaging to be taken from the fact that the neighborhood’s homeless population is the first group affected by the satanic awakening.

These are just a few examples from the first (into the second) act of the film. There are yet more examples of drifting claustrophobia throughout Prince of Darkness, like the surreal mirror world and the disorienting use of camera tilts in indoor settings. I am interested in Carpenter’s ability to find space in the city throughout his career, especially in politically charged urban action films like Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), Escape from New York (1981), and They Live!, and may take a crack at digging deeper into this claustrophobia motif in a more sustained effort some day.

Reblogged this on enemymindcontrol.

Oh excellent, thanks so much!