Photo credit: Blumhouse

Photo credit: Blumhouse

Is it an allegory for nuclear proliferation? A fever dream born from parental anxiety? A tale of nature reclaiming a post-industrial, near post-human world? Some combination of the three? One thing is certain: after 40 years, Eraserhead remains a film that leaves audiences saying, “I’m not sure what I just watched but I don’t feel good and I know I will never be the same again.” It’s a work in aesthetic counterpoint, as the ugliness of the narrative and its accompanying visuals is met with beautifully textured photography, exceptionally rendered make-up and props, and captivating set design. Lynch’s attention to detail, as displayed in each of these elements, helps elevate his film beyond art student avant-garde surrealist frippery and bring it into some emotionally affecting territory. As do the performances. Henry Spencer (Jack Nance) is a pathetic figure, insofar as he is a linchpin for any pathos found in such a disorienting and revolting film. Nance is helped along in this effort by playing off wonderfully erratic and upsetting turns from Charlotte Stewart, Jeanne Bates, Allen Joseph, and Judith Roberts. He’s also helped by his characteristic meekness, playing Henry with a quiet, subdued goofiness that suggests an alternate title for the film could be Charlie Chaplin Goes to Hell. After all, Hell, or at least some existential reflection on agency and the afterlife, is one of the film’s preoccupations. As is masculinity. And labor. And the aforementioned anxieties over destruction, nature, and procreation. For a run-time of 89 minutes and a surprisingly linear overall story arc, the film packs in a dizzying array of ideas and memorable visuals. And just when it seems it won’t be much more than a drifting, episodic curiosity, it explodes into a truly harrowing crescendo of gore that will likely haunt me for the rest of my days. In short, Eraserhead makes for one hell of a feature debut.

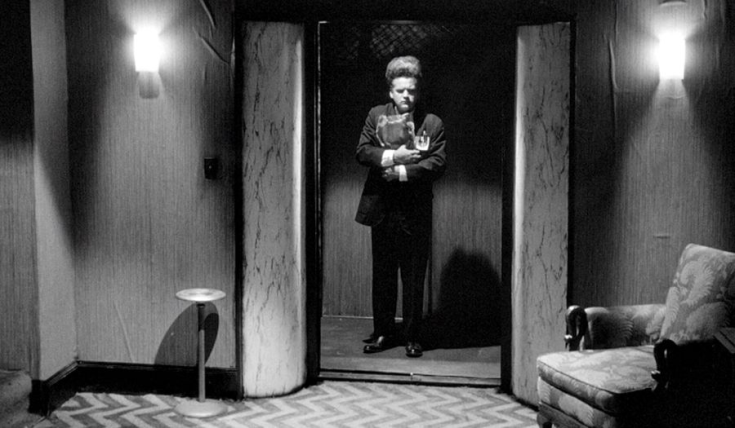

Despite its overall surreal pacing and imagery, the film has an authentic-feeling, hyper-real design. This is due in part to Lynch’s use of texture. A pock-marked tapestry of craters and chasms on a mysterious planet. A tangled mass of peat moss piled on a bedroom floor. A sickly man , shirking and twitching in the dark, covered in boils and scars (and played by all-star production designer Jack Fisk, though you wouldn’t know it even if you knew what Jack Fisk looks like). Even innocuous images like a puddle or a radiator. Every frame of Eraserhead is rendered in unsettling detail, drawing the eye despite presenting the viewer with some repulsive material. This is achieved mostly through lighting, set design, and some wickedly gross prop and makeup work. Cinematographer Frederick Elmes takes full advantage of the decision to shoot in black and white, filling the screen with a chiaroscuro so heavy it’d pull its subjects right out of the frame if it weren’t so precisely balanced. Lynch’s stagecraft skills are on full display, with sets that are just odd enough without distracting entirely, but he also does well to take his camera outside and highlight his ability to find some richly bleak industrial spaces. And one of the awful highlights of the film is the “baby,” a grotesquerie finely wrought in such stunning detail one wonders if there’s some truth to Lynch’s joke that it wasn’t made, but discovered by the crew one day while shooting. The notion of blurring the line between attraction and repulsion, of using a wide-ranging aesthetic toolkit to manipulate cognitive processes and force some reconsideration of what makes a thing “beautiful”, seems to be a preoccupation of Lynch’s. As he explains in a 1979 interview centered on the film, “I think that a lot of things that other people think are ugly, are beautiful. And if you look at them right, or if they’re sort of isolated, and put in a different context, they can be seen as shapes and textures and they’re beautiful.”

The overall effect is one of Lynch letting us in, or pushing us down, to a complex maze of hidden worlds. The camera drifts often, and leads the viewer into the shadows that dominate every frame, bringing them to see what’s on the other side. We are taken through a jagged hole in an ominous metal box to get a glimpse of the Man in the Planet, an agent of change who seems to control portions of Henry’s life by just pushing and pulling a few levers. We enter Henry’s radiator, where a deformed woman (Laurel Near) performs a stage routine in an eerie club (reminiscent of both the Red Room and roadhouse in Lynch’s Twin Peaks), enticing him with promises of Heaven but pretty much leading him to Hell. We sink into puddles, time and again, that raise questions of creation in the way they so often suggest the Primordial Soup. We are brought into these marginal worlds, and no good comes from it. It’s as though the viewer is being punished for participating in cinema’s campaign of voyeurism, turning the act of seeing into a practice of being complicit with violent absurdity. This creates a kind of trial on the nature of film, and especially on what’s accepted as tradition in the form. With its tight use of space, sparse dialogue, black-and-white photography, and old-timey Fats Waller organ music, the film seems conscious of Old Hollywood’s domineering influence. So it might be that the warping of voyeuristic engagement is a sort of reckoning with the sins of the motion picture industry. Or that Lynch is marking himself in his feature debut as a cinematic enfant terrible, tilting at anyone who thinks that film has always been and should remain a passive artform. I wonder if his training as a painter lends him an extra curiosity for and judgment of filmmaking, giving him a unique critical perspective and allowing him to “break the rules,” as it were. He fills his title sequence with a superimposed, translucent image of the title character. He uses strobe lights to throw figures around the frame, and sometimes jump cuts haphazardly to make them disappear altogether. Eraserhead pulls back curtain after curtain, and we’re left to wonder whether or not we ever should have taken a peek.

Watching Eraserhead has long been a sort of vocation for me. As someone who grew up and lives in the suburbs just outside of Philadelphia, I was always intrigued by this film that I’d heard was influenced by Lynch’s time in that city in its grimier days. As if the film and the city coexisted on this alien plane where I knew I needed to spend more time. Add to this the fact that Lynch and one of my brothers share an alma mater (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts) and some aesthetic sensibilities, and the result is a film that’s always felt personal to me even though I’d never seen it. How perfect, then, to pursue this vocational beacon and find such a delightfully horrific skewering of notions like finding meaning and holding things sacrosanct. I think this may prove to be a transformative experience for me in terms of my film comfort zone. It’s going to get ugly, and that’s just fine.